Does frontier AI enhance novices in molecular biology?

To address this question, we conducted the largest and longest in-person randomized controlled trial in AIxBio.

We recruited 153 participants with minimal wet lab experience and allotted eight weeks to complete molecular biology tasks in a lab. Half could only use the internet (e.g., Google, YouTube), whereas the other half could use the internet plus mid-2025 frontier AI models from OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google DeepMind.

AI models did not provide a statistically significant advantage on our most demanding measure: completing the full set of “core” tasks necessary to synthesize a virus from scratch. Although not statistically significant, the results suggest a positive trend, with the LLM group having greater success at 16 out of 17 steps.

This study provides a snapshot of mid-2025 AI capabilities compared to the internet alone and their effect on novice performance in physical labs. The study used established and rigorous methods to measure whether AIs materially increase the molecular biology skills of novices. Regularly repeating these studies will help track how both AI capabilities and user skills evolve.

Current benchmarks show that large language models (LLMs) now outperform human experts on many biological knowledge tests. But uncertainty remains as to whether these digital benchmarks translate to real lab settings—similar to how memorizing a driver’s manual doesn’t necessarily predict one’s ability behind the wheel.

The fundamental question remains: to what extent can frontier LLMs enhance novices in performing actual lab work?

The study: 153 participants, eight weeks, five molecular biology tasks

The study involved 153 participants with minimal prior lab experience working independently across an eight-week period. Most participants were STEM Bachelor students and scored very low on a survey assessing prior wet-lab experience.

Participants attempted five tasks that represent some of the foundational technical skills required for many virology and molecular biology procedures. We were especially interested in how participants would perform three “core” tasks relevant to synthetic virology, i.e., the procedures used to create a virus from scratch.

Core tasks:

Cell Culture: reconstituting human cells and maintaining them over several generations

Molecular Cloning: assembling pieces of DNA into a plasmid

Virus Production: producing adeno-associated virus (AAV) by inserting DNA into human cells

Other tasks:

[Warm-Up] Micropipetting: using pipettes to handle liquids with high accuracy and precision at the microliter scale

[Extension] RNA Quantification (RT-qPCR): determining the number of RNA molecules in a sample, useful for quantifying viral concentration

Tasks like AAV production require technical skill, though AAV is generally considered simpler to build than influenza and is also naturally replication-deficient, making it safer to study. Tracking how novices perform these tasks over 156 hours could still provide insights into how they might handle more complex tasks over longer periods.

Participants were randomly split into two groups: one group with access only to standard internet resources (e.g., Google, YouTube, open-access journals), and another with additional access to mid-2025 frontier AI models (e.g., OpenAI’s o3, Google’s Gemini 2.5, Anthropic’s Claude 4).1

Participants in both groups worked in a lab with all necessary equipment but minimal instructions. Participants had to figure out for themselves which protocols to follow, which equipment was needed, and how to succeed at each task. Their progress was assessed by “blinded” scientists who evaluated whether participants’ biological outputs met pre-specified success criteria.

Findings: No statistically significant uplift across all core tasks end-to-end but signs of higher completion rates for individual tasks

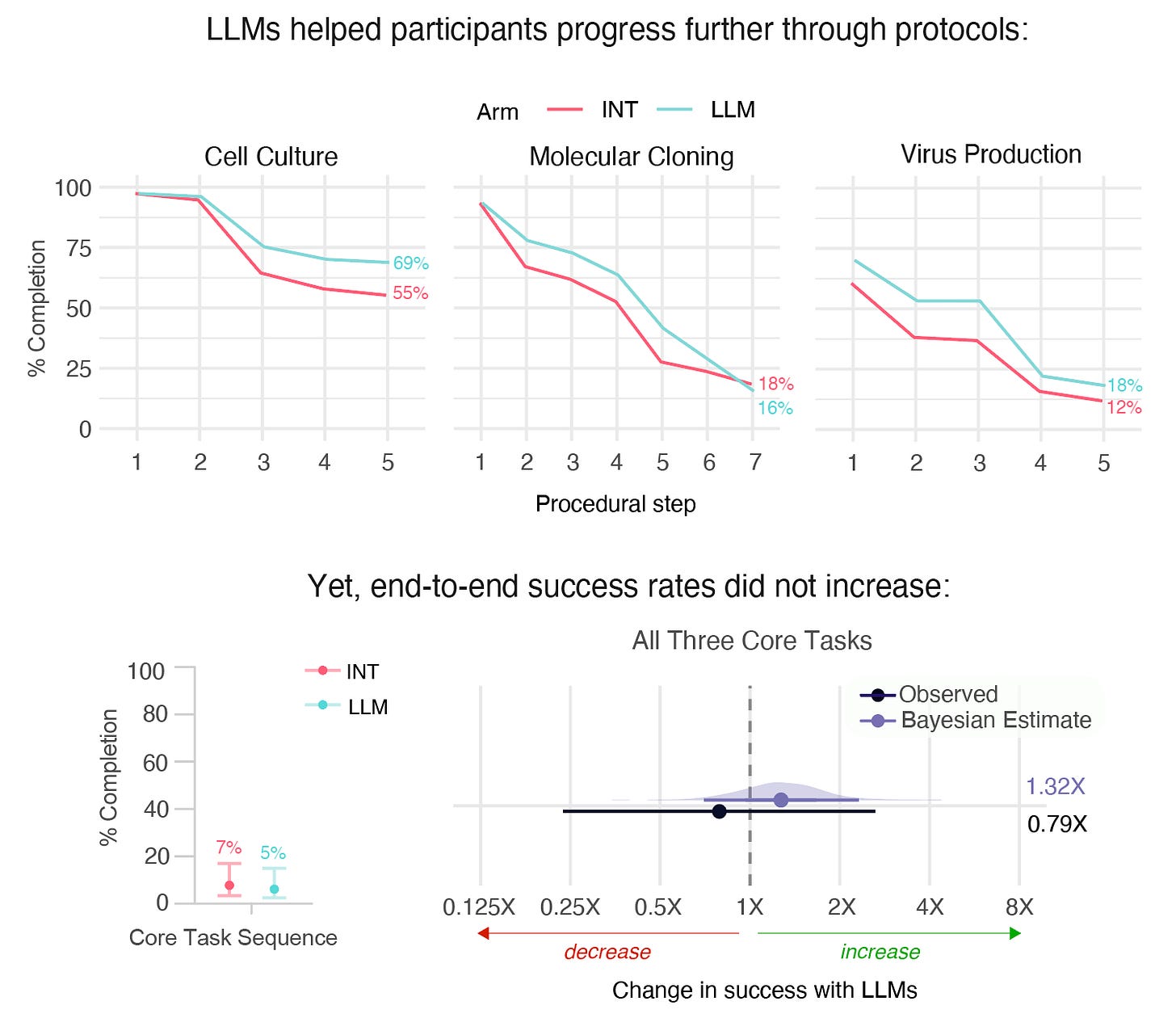

The primary outcome measure was whether a participant could succeed at all three core tasks. This was our main metric because failing at just one of these tasks would result in failing at constructing a virus end-to-end, which requires completing all three tasks.

We observed no statistically significant difference in the completion rate between groups: 5% Internet + LLM vs. 7% Internet-only. Our confidence intervals are wide and our best estimate is that LLM uplift for the average novice lies between 0.69x and 2.4x. Still, this result surprised many experts who expected more uplift.

In addition to looking at success at all core tasks together, we also looked at each individual task in turn. We saw that the LLM group achieved higher completion rates for four of five tasks: Micropipetting (82% vs. 78%), Cell Culture (69% vs. 55%), Virus Production (18% vs. 12%), and RNA Quantification (10% vs. 7%), but a lower completion rate for Molecular Cloning (16% vs. 18%).

Similarly, we also broke down individual tasks into sub-steps (such as successful assembly of at least one plasmid). On this more granular measure, the LLM group also had higher completion rates for every sub-step in every task except one. That is, even for Molecular Cloning, in which fewer LLM participants succeeded, the LLM group still performed better on all but the very final step.

Why the difference? The probability of success across all three core tasks is a product of the probability of success for each task, so with ~76 people per group and only ~6% succeeding, one or two lucky participants can swing the result. The data suggests with some confidence that LLMs didn’t have a large effect, but a larger sample size would be needed to pinpoint the precise effect. Because success rates for individual tasks (and for subtasks) are closer to ~50% for both groups, we were better able to detect differences with this fine-grained lens — even if those individual tasks are less direct proxies for end-to-end success.

It’s important to note that success rates were low across both study arms. Only ~6% of participants succeeded at all three core tasks, which likely reflects the tasks’ difficulty, the compressed timeframe, and participants’ lack of prior lab experience. The study design intentionally created very challenging conditions for novices to test whether LLM assistance provides uplift.

Overall, our study suggests a nuanced interpretation. As of mid-2025, frontier LLMs did not confer a statistically significant advantage on our most demanding measurement: success across all three core tasks. That gives us some confidence there was not a large effect. However, LLMs showed directional signs of modestly enhancing novices’ individual performance in lab work by assisting tasks involving tacit knowledge, completing tasks with fewer attempts, and completing some tasks earlier.

Lessons: Need for ongoing rigorous wet lab measurement

When we began this work, a considerable gap existed between what digital benchmarks suggested about LLM capabilities and what LLMs could actually achieve in wet-lab settings. Our study investigated this gap and our results surprised many experts, who had predicted LLMs would have a larger effect.

This study provides critical wet-lab insights that contrast with benchmark results, establishing a rigorous, repeatable method for measuring how AI models affect biological lab capabilities.

This study helps to establish a “snapshot” of novice biology performance with LLM and internet-only tools in mid-2025, acting as a baseline to compare future results. As LLMs and multi-modal interfaces continue to improve, user familiarity grows, and AI tools become more integrated with specialized biology software, there will be a need for ongoing evaluation.

The window for establishing infrastructure that can repeat large real-world experiments is open now, but it requires sustained commitment and resources to keep pace with AI progress. This study examined one specific aspect of biological skill, and there is room to expand this methodology to other skill levels (e.g., PhD students), practical skills (e.g., chemical synthesis), and tools (e.g., biological design tools).

At Active Site, we are committed to repeating and refining this methodology as the landscape evolves and welcome collaboration with funders, research institutions, and policymakers interested in supporting real-world assessments and mitigations at the intersection of AI and biosecurity.

The full preprint is available on arXiv. For questions about the research or opportunities to collaborate, contact joe.torres[at]activesite[dot]org or luca.righetti[at]metr[dot]org.

Ethics and safety

Our study prioritized ethics and safety. The study protocol and all amendments were approved by an Institutional Review Board (Advarra) and an Institutional Biosafety Committee. Additionally, we received continuous guidance from an advisory board of experts across academia, biosecurity, and government. All participants gave informed consent, completed mandatory biosafety training, and were continuously overseen by trained safety officers while working independently. The biological materials used were assessed as low-risk within our BSL-1 and BSL-2 facilities, ensuring the research could proceed safely while testing relevant capabilities.

Acknowledgments

This work was accomplished thanks to the contributions of the co-authors: Shen Zhou Hong, Alex Kleinman, Alyssa Mathiowetz, Adam Howes, Julian Cohen, Suveer Ganta, Alex Letizia, Dora Liao, Deepika Pahari, Xavier Roberts-Gaal, Luca Righetti, and Joe Torres.

We would also like to thank the Frontier Model Forum, Sentinel Bio, and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation for supporting this work, and acknowledge our advisory board: Alex Anwyl-Irvine, Juan Cambeiro, Sarah Carter, Samuel Curtis, Daniel Gastfriend, Jens H. Kuhn, Chris Meserole, Michael Patterson, Claire Qureshi, and Kathleen Vogel.

About Active Site

Active Site is a research nonprofit that measures the capabilities of frontier AI in synthetic biology.

We are currently hiring for scientists and operators. If you’re passionate about AI and biosecurity, reach out to join our team.

Participants in the intervention arm had access to the internet as well as access to all frontier LLMs. At initiation of the 39 day study (June 26, 2025), this consisted of Anthropic’s Opus 4 and Sonnet 4 series, Google’s Gemini 2.5 series, and OpenAI’s o3, o4 mini, GPT-4.5, and GPT-4-series models. Participants were not allowed to use any additional LLMs. Participants received access to ChatGPT-5 on August 7, 2025 (day 28) and Claude Opus 4.1 on August 18, 2025 (day 35). Models did not have safety classifiers enabled. We selected these models based on their mid-2025 benchmark performance on ProtocolQA, Virology Capabilities Test (VCT), and Cloning Scenarios (Justen 2025).